At what point in life must you be willing to sacrifice happiness for survival? Ironbound, a play by Martyna Majok currently in its west coast premiere at the Geffen Playhouse in Los Angeles, tells the story of Darja (Marin Ireland), a Polish immigrant struggling to build a life for herself in New Jersey. Whether it is actually Darja’s story or the story of a woman’s life being dictated by the men she surrounds herself with is another question, and the answer is a bit troubling.

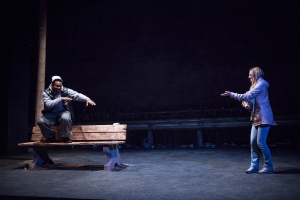

Ironbound is told in a series of non-linear scenes that all share the same setting—a bus stop near a factory in Elizabeth, NJ. We see Darja at three points throughout her life—in 1992, at age 20, in 2006, at age 34, and in 2014, at age 42. Darja speaks in broken English that seems self-taught, although her speech patterns evolve depending on when the scene takes place. She tries to make ends meet by cleaning houses, and, for a time, working in the nearby factory, which shuts down at some point between 1992 and 2006 due to the changing economy. Darja at 42 has only one concern— the wellbeing of her 22-year-old son, who has run away, taking her car with him. As snapshots of her life slowly paint a picture of how she came to be where she is, and why her relationship with her son is so tumultuous, we meet three men who have affected Darja’s life, whether for years or just for a few minutes.

The first is Tommy (Christian Camargo), a postal worker who has been 42-year-old Darja’s live-in boyfriend for nearly seven years. He’s more than a bit of a schmuck and a serial cheater, but he has a steady job, and is able to help pay the rent. Then there’s Maks (Josiah Bania), a fellow immigrant and 20-year-old Darja’s first love. His head is perpetually in the clouds and he dreams of leaving New Jersey for Chicago to pursue a music career, which does not seem smart or realistic to Darja, especially once she gets pregnant. The third is Vic (Marcel Spears), a high school-aged prostitute whom Darja encounters at a particularly low moment when she is 34. Their interaction is brief but memorable, illuminating Darja’s frustrations with class and wealth in the United States.

Director Tyne Rafaeli does a great job at differentiating the time periods, a common pitfall for many plays that attempt it. This timeline is clear and never hard to follow, thanks to subtle lines of dialogue and small shifts in hair and wardrobe. One great indicator is the evolution of the cell phones used in 2004 versus 2016, with flip phones making way for iPhones. Ireland is giving a fine performance, particularly in drawing a contrast between Darja at different stages of life and levels of optimism. Darja is just trying to get from one day to the next. She’s pragmatic and determined, yet stagnant. She makes similar mistakes again and again, nearly all of them involving the men she chooses to associate with.

At no point in the story does Darja seem to consider a means of survival that does not involve finding a man to depend on. She even at one point self-sabotages her job in a seemingly unnecessary way, putting herself in an even more desperate situation. Perhaps this is a harsh interpretation. Darja goes through a lot, and certain events, such as most factory work in the United States being outsourced to foreign markets, are beyond her control. She stubbornly refuses money from a stranger as a point of pride, and yet is willing to set her dignity aside when it comes to her relationships. It seems the intended point may be that in this country, both women and immigrants are at an often unsurmountable disadvantage, which is absolutely true. While this view may be sobering, it feels extremely pessimistic now, in 2018, when so many are standing up for women’s rights and immigrant rights.

Even one life decision not dictated by one of her boyfriends turned husbands would have helped me to see Darja in a more active light, but she is just remarkably passive throughout. Terrible things happen to her and she reacts by gravitating towards another man who does not respect her and mistreats her, and it is very frustrating to watch. She repeatedly accepts relationships that fall at different points on the spectrum of abuse because it is the way she knows how to get by. Her reactionary nature might not seem as problematic if we ever saw her with another woman in her life, but the only other females in her story, a friend at the factory and an employer whose house she cleans, are merely mentioned and never seen. The idea of an immigrant woman trying to get by in a changing world and economy over a period of 22 years is compelling and important, but the frustrating nature of Darja’s character combined with the narrative choice to surround her only by distasteful men prevents any larger point from being made.

Ironbound runs through March 4th at the Geffen Playhouse. The running time is 80 minutes, no intermission. Tickets range from $25-$90 ($25 for college students) and can be purchased here.

What a profound misreading of this story.

Darja drives this entire play. She makes the discoveries. She gives the ultimatums. You’d be hard pressed to find a more active female protagonist onstage in America right now.

Whether or not you’re “interested” in seeing the story of a working class immigrant woman whose ability to survive is inherently and inextricably tied to a patriarchal power structure is irrelevant, particularly when, in spite of the movements you mention for immigrant and women’s rights, the plight of immigrants in this country (especially female ones) is more fraught than ever. The #metoo movement, as crucial and powerful and amazing as it is, has yet to substantively reach women like Darja. ICE is arresting and deporting children, Dreamers, daily. The movements you’re talking about may never reach women like her. To pretend otherwise is to be complicit.

The truth is, for some people, there are simply fewer choices. It may be unsavory, but that’s what millions of people face daily.

This review betrays both a profound ignorance of the current day-to-day life of immigrants in this country, and the apparent privilege of the person writing it.

The infuriating truth is that compromises for security are made every day by people all over the world. Often those compromises involve a romantic partner. And often, “choice” doesn’t factor in that much when options are so limited. Do you want to eat? Do you want a place to live? Sometimes you’ve gotta shack up.

This is what angers me: that women like Darja often don’t have a good option to choose from. That non-ideal partnering can be necessary to survive. That people, through trauma, can be conditioned to act against their own self-interest in the name of preservation or stability. That sometimes all forks in the road lead to some form of self-destruction.

This may not be the narrative you want to see. Women like Darja also wish for different life narratives.

All this said, maybe most importantly, the play doesn’t ask us to like Darja, or consider her a hero. Far from it. It asks us to consider her. Period.

For my money, this review epitomizes lazy contrarianism. There are miracles happening onstage at Geffen Playhouse right now that go well beyond the effective use of a flip phone.

LikeLike

Thank you for reading and for your comment and I respect your opinion. As a critic, it is my job to offer my opinion. This review is just that, my opinion. I do not expect everyone to agree with me.

LikeLike

It’s in the spirit of critical discourse that I’m responding.

Saying that a particular narrative isn’t one you’re interested in seeing isn’t criticism. It’s an expression of the kind of character or story you’d like to see, not an honest response to the one you were presented with.

What I learned from your review was that you didn’t like the choices the protagonist made. That her decisions made you uncomfortable.

Well, that’s theater. Or anyway, that’s good theater.

What a gift! Seldom do we get to see protagonists, particularly female ones, who don’t fall squarely into the Madonna/Harlot archetypes.

Critics are absolutely entitled to their opinions. However, as pieces of criticism, those opinions ought be accountable to accurate dramaturgy. And if taking the playwright to task for her portrayal of the current struggles of female immigrants in this country is an aspect of that criticism, we should see hard evidence that the critic has a more expansive, specific, fact-based understanding of that issue than the playwright, a first generation female immigrant to this country.

LikeLike

Part of being a critic is commenting on works depicting experiences outside your own. If critics were only allowed to write about stories and characters they have personally experienced in the same way as the creatives, theatre criticism would not exist.

Darja did not make me uncomfortable, and I never said the play tried and failed to make her into a hero. You say the point is to consider her, and I considered her quite carefully before writing this review. It is very disappointing to me to hear my work described as “lazy contrarianism,” because that is not what I do as a critic. I hope, if you are at all interested in reading any of my other reviews, that you will see this. My opinions are not published anonymously, and I do not take that lightly.

I see over 50 shows a year. Of the last six shows I have seen, only one had more than one woman in its cast, and in that instance, only one female character had a name. I hope to write a more general piece in the coming days about this particular frustration. As I pointed out in my review, I would have liked to have seen a view of Darja’s experiences that was not so focused on men, especially considering she tells multiple stories about other women in her life. Those are perspectives I would have liked to have seen included. I critiqued narrative and character choices because, to me, they were not the most effective when it came to communicating what I interpreted the message of the play to be. The problems I described were regarding this particular, fictional story, and the way the playwright chose to tell it. They are not a generalization about the very real issues presented in the story, issues I firmly believe are important.

LikeLike